Geoscientists discover 500,000 years of climate history in central Mexico

The effects of climate change on tropical regions are still poorly understood. However, tropical regions are among the most populated areas in the world. Researchers at the Leibniz Institute for Applied Geophysics (LIAG) have now created both an age-depth model and a moisture distribution for the last 500,000 years from one of the oldest lakes in central Mexico, Lake Chalco.

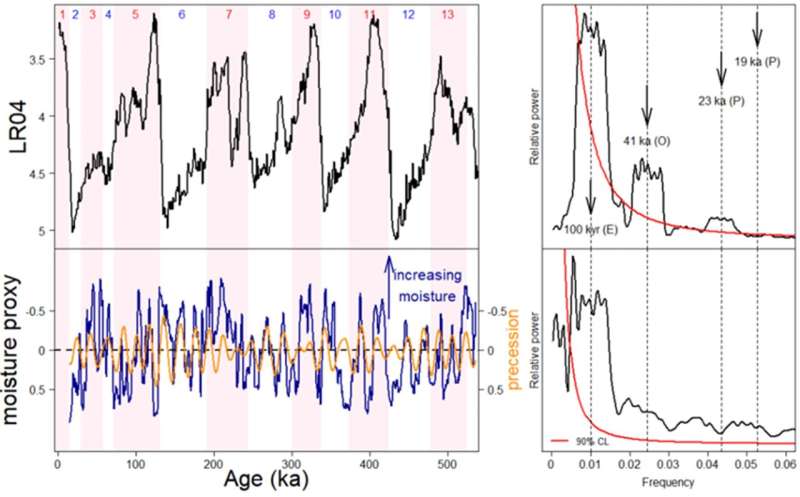

The results are clear: Central Mexico experienced recurrent dry periods related to Earth's natural wobble. The researchers have published their work in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

Central Mexico, because of its mild climate and fertile soil, has been continuously populated by humans since colonization of primary civilizations and remains an area with one of the highest population concentrations in the world. The combination of rapid population growth, anticipated future increases in air temperature and likelihood of droughts in central Mexico suggest that this will remain a region strongly impacted by changing climate.

Improved understanding of both the mechanisms contributing to the present climate change and its consequences for the biosphere, including human society, will not only provide the knowledge required to cope with its effects, but may also shed light on the forces that have driven similar events in the past.

In 2016, downhole measurements were taken in a borehole approximately 500 meters deep in Lake Chalco in an area on the outskirts of Mexico City. The research team used borehole geophysics, which measures the physical properties of sediments, to extract paleoclimate signals from lacustrine deposits in the upper 300 meters to determine past climate conditions.

This is the first time that borehole geophysical data has been used to reveal the history of moisture content in lake sediments, providing insight into 500,000 years of climate history in central Mexico. In addition, the research team also dated Lake Chalco sediments using astrochronology, a technique for calibrating sediments using Earth's orbital cycles, the regular wobbling motion of Earth's orbit around the sun.

The results indicate that central Mexico regularly experienced a dry period during the last 500,000 years, when Earth's orbit was at its most circular.

The specific geomorphology of central Mexico, because of emergence of a long series of volcanic arcs due to the subduction of Pacific Oceanic Plate beneath the North American continental Plate, allowed for the formation of an extensive interior drainage basin nearly one million years ago. In the present day, this geological formation is called the Valley of Mexico. Since its formation, the water has remained in this basin and covered nearly 1,500 square kilometers of the valley floor.

The water level in the lake oscillated in response to alternating warm and cool periods in Earth's paleoclimate. Earth has experienced cold (glacial) and warm (interglacial) periods in roughly 100,000-year cycles for at least the last 1 million years. During the warm periods, higher precipitation in central Mexico raised the lake water level to 100 meters, and during the cold periods, the water level dropped to a few meters because of droughts.

"The lake sediments trace the planet's history and preserve clues that tell of past climate and environmental conditions. Through this study, we can identify how variable climate shifts were in the past and how the environment responded," explains Dr. Mehrdad Sardar Abadi, MexiDrill project coordinator at LIAG. "The successful application of the methodology and the results also help future paleoclimate studies that can build on it."

Before the arrival of the Spanish, the Basin of Mexico was occupied by the Aztec people, who built a large city called Tenochtitlan on and around the lake system. In the early 1600s CE, the Spanish drained most of the lake system in an attempt to control flooding. Present day Lake Chalco is a shallow marsh, which occupies an area of less than 6 square kilometers south of Mexico City.

An important source of water supply in Mexico City comes from underground aquifers formed among the ancient lacustrine sediment that is being drained at an irreplaceable rate. As a result, Mexico City is sinking downward rapidly at about half a meter per year. The water crisis in Mexico City has become an ongoing problem with depleting the underground aquifers, and is sinking the city.

More information: Mehrdad Sardar Abadi et al, An astronomical age-depth model and reconstruction of moisture availability in the sediments of Lake Chalco, central Mexico, using borehole logging data, Quaternary Science Reviews (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2022.107739

Journal information: Quaternary Science Reviews

Provided by Leibniz Institute for Applied Geophysics