This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

NASA's Roman mission gears up for a torrent of future data

NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope team is exploring ways to support community efforts that will prepare for the deluge of data the mission will return. Recently selected infrastructure teams will serve a vital role in the preliminary work by creating simulations, scouting the skies with other telescopes, calibrating Roman's components, and much more.

Their work will complement additional efforts by other teams and individuals around the world, who will join forces to maximize Roman's scientific potential. The goal is to ensure that, when the mission launches by May 2027, scientists will already have the tools they need to uncover billions of cosmic objects and help untangle mysteries like dark energy.

"We're harnessing the science community at large to lay a foundation, so when we get to launch we'll be able to do powerful science right out of the gate," said Julie McEnery, Roman's senior project scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "There's a lot of exciting work to do, and many different ways for scientists to get involved."

Simulations lie at the heart of the preparatory efforts. They enable scientists to test algorithms, estimate Roman's scientific return, and fine-tune observing strategies so that we'll learn as much as possible about the universe.

Teams will be able to sprinkle different cosmic phenomena through a simulated dataset and then run machine learning algorithms to see how well they can automatically find the phenomena. Developing fast and efficient ways to identify underlying patterns will be vital given Roman's enormous data collection rate. The mission is expected to amass 20,000 terabytes (20 petabytes) of observations containing trillions of individual measurements of stars and galaxies over the course of its five-year primary mission.

"The preparatory work is complex, partly because everything Roman will do is quite interconnected," McEnery said. "Each observation is going to be used by multiple teams for very different science cases, so we're creating an environment that makes it as easy as possible for scientists to collaborate."

Some scientists will conduct precursor observations using other telescopes, including NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, the Keck Observatory in Hawaii, and Japan's PRIME (Prime-focus Infrared Microlensing Experiment) located in the South African Astronomical Observatory in Sutherland. These observations will help astronomers optimize Roman's observing plan by identifying the best individual targets and regions of space for Roman and better understand the data the mission is expected to deliver.

Some teams will explore how they might combine data from different observatories and use multiple telescopes in tandem. For example, using PRIME and Roman together would help astronomers learn more about objects found via warped space-time. And Roman scientists will be able to lean on archived Hubble data to look back in time and see where cosmic objects were and how they were behaving, building a more complete history of the objects astronomers will use Roman to study.

Roman will also identify interesting targets that observatories such as NASA's James Webb Space Telescope can zoom in on for more detailed studies.

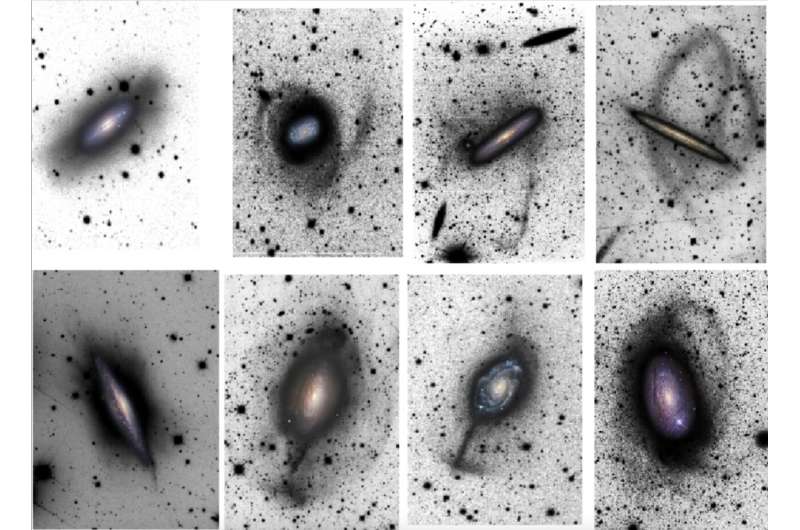

It will take many teams working in parallel to plan for each Roman science case. "Scientists can take something Roman will explore, like wispy streams of stars that extend far beyond the apparent edges of many galaxies, and consider all of the things needed to study them really well," said Dominic Benford, Roman's program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

"That could include algorithms for dim objects, developing ways to measure star positions very precisely, understanding how detector effects could influence the observations and knowing how to correct for them, coming up with the most effective strategy to image stellar streams, and much more."

One group is developing processing and analysis software for Roman's Coronagraph Instrument. This instrument will demonstrate several cutting-edge technologies that could help astronomers directly image planets beyond our solar system. This team will also simulate different objects and planetary systems the Coronagraph could unveil, from dusty disks surrounding stars to old, cold worlds similar to Jupiter.

The mission's science centers are gearing up to manage Roman's data pipeline and archive and establishing systems to plan and execute observations. As part of a separate, upcoming effort, they will convene a survey definition team that will take in all of the preparatory information scientists are generating now and all the interests from the broader astronomical community to determine Roman's optimal observation plans in detail.

"The team is looking forward to coordinating and funneling all the preliminary work," McEnery said. "It's a challenging but also exciting opportunity to set the stage for Roman and ensure each of its future observations will contribute to a wealth of scientific discoveries."

Provided by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center